TL;DR: if you use git-annex and have a reMarkable 2 tablet, you might find this special remote useful.

Too many pdfs …

It is a truth universally acknowledged (among some people, at least), that pdfs have an unfortunate tendency to pile up, forming unstructured heaps in the “Downloads” directory where nothing that has once been read can ever be found again. Inevitably, things become much worse once one attempts to sort a few of them into their own directory, renames files, moves computers …

For a couple years now, git-annex has been

my way to tackle this issue: I have a single git repository which contains

everything I read (and a lot more I don’t); git-annex dutifully takes care of

tracking these files, of moving

the entire thing to new computers, of checking I have copies on other systems before

deleting any local copies, etc — all I have to do is remember to check files into git.

git annex assistant

In fact, git annex comes with an “assistant” which runs as a daemon so it can

check in new files automatically and even sync them to other devices, but I still

like doing this by hand, and leave notes for myself in the commit messages.

In a wild twist, the thing designed to be a good archival tool turns out to be good at archival work.

Reading

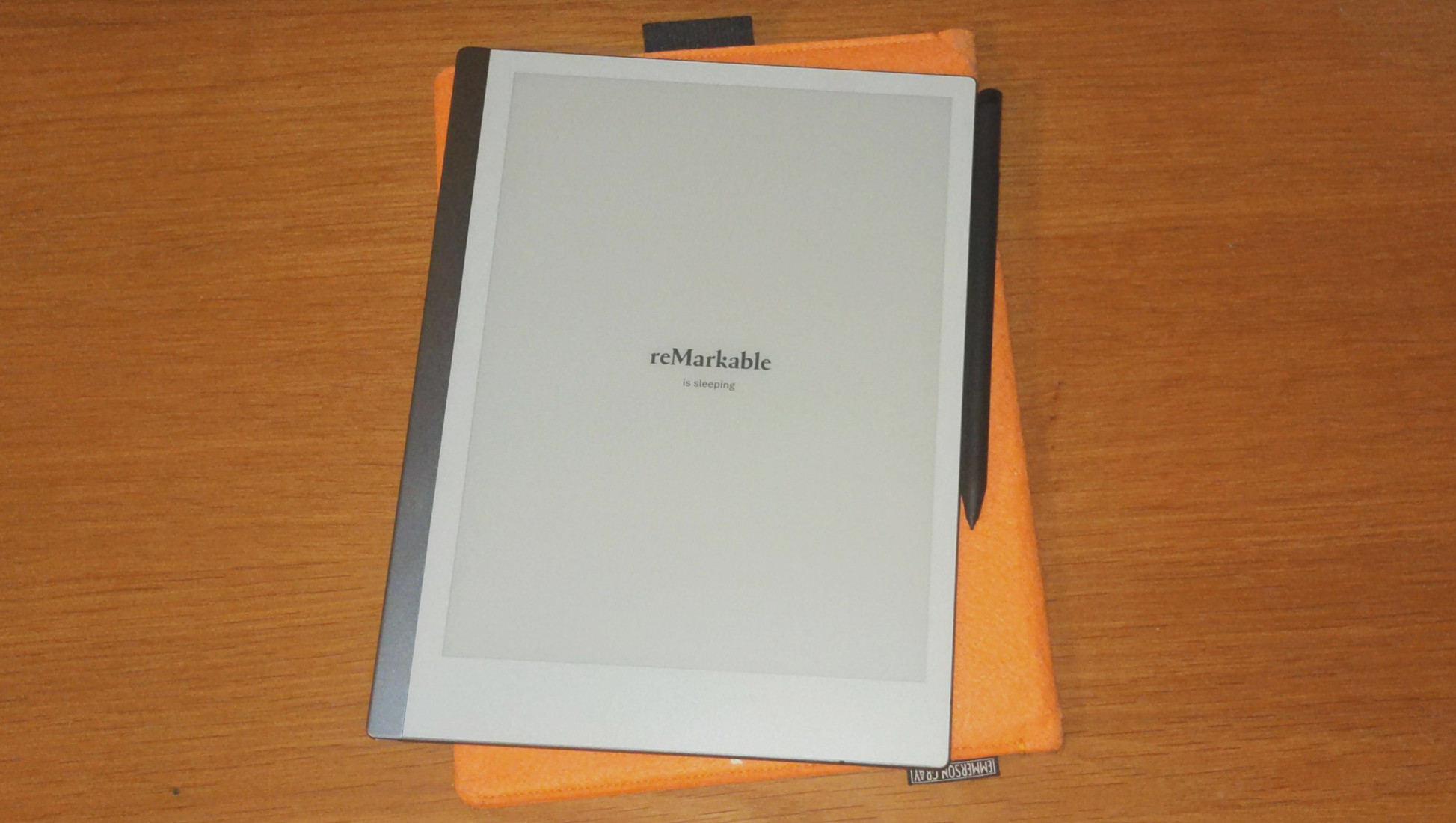

I read a lot, but LCD screens strain my eyes. This is a general problem, but for reading there’s off-the-shelf solutions:

Conveniently, this runs a reasonably ‘standard’ Linux — including familiar busybox and systemd — and it also runs a pre-configured ssh daemon out of the box.

Happily, while the UI software is proprietary, I am also not beholden to the company’s commercial cloud service to sync files to the device — someone has already re-implemented that (only one project among many; people have also written a package manager and even entirely new UIs).

Except – I don’t want any cloud service, be it self-hosted or not! I don’t even connect the thing to the internet very often — surely, if I can have an ssh session via its USB port, that should be enough?

Special remotes

git annex has an obvious way to handle such things:

special remotes.

If it can store and retrieve objects by a key (an identifier usually based

on some hash), git annex can be taught to consider it external storage

and push files to it — without caring how it looks on the ‘other side’.

So let’s just make the other side that tablet?

Writing a new special remote is as easy as implementing the dedicated

line protocol,

which git annex uses to talk to a sub-process via std IO.

“as easy as”

of course belies that every line protocol will inevitably have unspecified handling of white space

Presumably the world would be a better place had we all learnt the art of never not bothering with a proper grammar.

Alas!

(suffice it to say I had fun)

For extra fun, I decided to write mine in Rust, without any external

crates, i.e. only using things from std (calling a few external program

to handle e.g. ssh and uuids). This works surprisingly well: rust

makes for a – somewhat verbose – scripting language, too.

Xochitl ipan quixichihua in amatl

File structure

Xochitl, the tablet’s UI, expects documents to be stored under

~/.local/share/remarkable/xochitl as a flat list:

$ ls .local/share/remarkable/xochitl

-rw-r--r-- .local/share/remarkable/xochitl/d1e71a92-3ab8-4455-9233-d84c06f3997a.content

-rw-r--r-- .local/share/remarkable/xochitl/d1e71a92-3ab8-4455-9233-d84c06f3997a.local

-rw-r--r-- .local/share/remarkable/xochitl/d1e71a92-3ab8-4455-9233-d84c06f3997a.metadata

-rw-r--r-- .local/share/remarkable/xochitl/d1e71a92-3ab8-4455-9233-d84c06f3997a.pagedata

-rw------- .local/share/remarkable/xochitl/d1e71a92-3ab8-4455-9233-d84c06f3997a.pdfOne displayed document is several files, grouped by a common UUID — the pdf file itself, metadata, hand-drawn notes for each page of the document, tags, …

To store a new

one, the special remote can derive a stable UUIDv5 from the item’s key, namespaced

to the special remote itself (conveniently, git annex assigns each special

remote instance its own UUID already, which works well for this).

File content

Second step: minimal skeletons of the other files, just enough to make xochitl

happy and display our document. It turns out a few fields in .metadata and

.content are enough; xochitl will fill in the rest by itself.

{

"createdTime": "970351200",

"lastModified": "978303600",

"lastOpened": "{time}",

"lastOpenedPage": 0,

"parent": "",

"pinned": false,

"type": "DocumentType",

"visibleName": "Nahuatl As Written"

}.metadata

{

"coverPageNumber": 0,

"documentMetadata": {},

"extraMetadata": {},

"fileType": "pdf",

"fontName": "",

"pageTags": [],

"tags": [],

"textAlignment": "justify",

"textScale": 1,

"zoomMode": "bestFit"

}.content

One issue: .metadata sets the document’s name, as shown on the tablet.

But a special remote is nothing more than a

hash table: it knows items by key, not by any title or name, and won’t be told

anything as helpful as a file name.

Document names

So where to get a recognisable name?

I tried extracting the pdf’s embedded title, but it turns out this is too often missing or unhelpful (who needs tens of documents titled “Microsoft Word Document” in their listing?).

At this point I got a little stuck, but luckily, the protocol’s spec has an ‘export/import’ appendix, for this exact case: special remotes which also look like file listings, not only like hash tables.

Its operations are broadly similar to their ‘normal’ store/retrieve siblings,

but each also receives a file name to be freely used by the remote. For the tablet,

just taking the file name (without extension) seems good enough.

All this requires is that the special remote is initialised with exporttree=yes. Problem solved?

… well, mostly. This appendix is only half-done, and only the export operations

are specified, testable, and implemented in git annex; the whole ‘import’

section is an unimplemented draft.

I hereby declare getting files back out from the tablet to be a problem for future me.

Pushing to the device

Having set up the file structure, all that’s left is funneling it over ssh. Thankfully, this is as easy as it possibly could be:

With all this done, it’s time to git annex testremote (but do it in a sandbox

— or a VM test — else there’s a good chance of leaving litter behind if

anything was wrong).

git annex export & git annex wanted

One final issue: using the export operations allows us to use file names,

but the usual git annex copy & friends now no longer work: Any special remote

initialised with exporttree=yes has to be used with git annex export, which

can only operate a git branch or revision (or a subtree thereof), but not on

a single file.

Happily, git annex has a concept of filtering, which the export will respect:

Thanks to a friend for pointing this out! I was getting quite frustrated when I discovered this.

git annex metadata can attach little tags to files in git annex’s repository.

git annex wanted lets one specify which files a remote “wants” to store;

files that don’t match aren’t exported.

So all I need to do is git annex wanted <specialremote> "metadata=amatl=store"

once, and then git annex metadata -s amatl=store <filename> to mark new files

for transfer, and then git annex export (or simply git annex sync) to push

all new files to the device.

All done?

Well, not quite. Now I can read pdfs, but would it not be nice to also get any notes I draw on them back into the repository?

As mentioned, the “import” section of the protocol spec is still a draft, and unimplemented; there’s some additional complexity in that the tablet’s format for drawings is prorietary, although people have reverse-engineered it.

Perhaps I’ll look at this at some point in the future; I’m not sure if doing this

via git annex import wouldn’t be stretching the concept of special remotes a

little too far — do I really want to replace the entire content-addressed pdf in

git annex’s store every time I draw a new line on it? — but for now, that’s it.