Connection to ICE 4711 today on track 8, on the same platform directly opposite.

How reassuring to hear these words — but often they’re not there. Perhaps there was a surprising last-minute track change, or train staff isn’t sure either, or someone simply forgot, or you’re on a regional line where this kind of announcement is simply never done at all. Or perhaps (my personal favorite) the connection you’re intending to take was never meant to be possible in the first place.

Caveat:

To tame the otherwise overwhelmingly large scope, this post will limit itself to stations operated by Deutsche Bahn, i.e. mostly stations in Germany.

And suddenly you really need to know if tracks 3 and 4 are on the same platform in a station you’ve never been in before.

This post will describe how to solve this problem using data from Open Street Map (OSM), and use it as an excuse to learn some OverpassQL along the way. Since I happened to already run a search engine for German railway stations (who doesn’t?), you can also use the result simply by visiting bahnhof.name to get a list of platforms for your favorite station.

The Shape of the Problem

For the benefit of everyone who does not feel an innate sense of comfort in the liminal spaces which lurk at the edges of large rail yards (are you, perhaps, normal about trains?), I should perhaps explain how this is a problem at all. Because, well, aren’t tracks just numbered?

And indeed, usually they are. Occasionally even sequentially. Except when they’re not – almost all railway stations in Europe are a confusing, organically-grown mess, often more than a century old, and have had tracks removed, added, renamed, jumbled around, re-purposed, or even forgotten about entirely several times already.

So while tracks are usually numbered, sometimes track 3 simply no longer exists (but track 4 does). Or track 3 does exist, but is now only used for trains going through the station without stopping, and no longer has a platform next to it. Maybe there’s an additional track 1a at the far end of the platform with track 1. Or maybe track 1a just means one half of track 1, and the other half is called 1b. Maybe there is a track 108 next to track 8. Or maybe there is a track 101 at the far end of the station, for no obvious reason at all.

Or maybe you’ve stumbled into an unforgiving beast such as Kaiserslautern Hauptbahnhof, which has tracks 1 through 5, tracks 8 and 10, and also 39, 40, 41, 42, 45, and 120. Good luck guessing which of these are at the same platform (or even how the platforms are positioned relative to each other) if you’ve never seen it on a map. The signage at the station can only help so much.

So it seems worthwhile to invest a little time into this problem. Surely it’s possible to find an easier way to answer “are these two tracks next to each other” than fiddling around with maps and signage?

Related Work

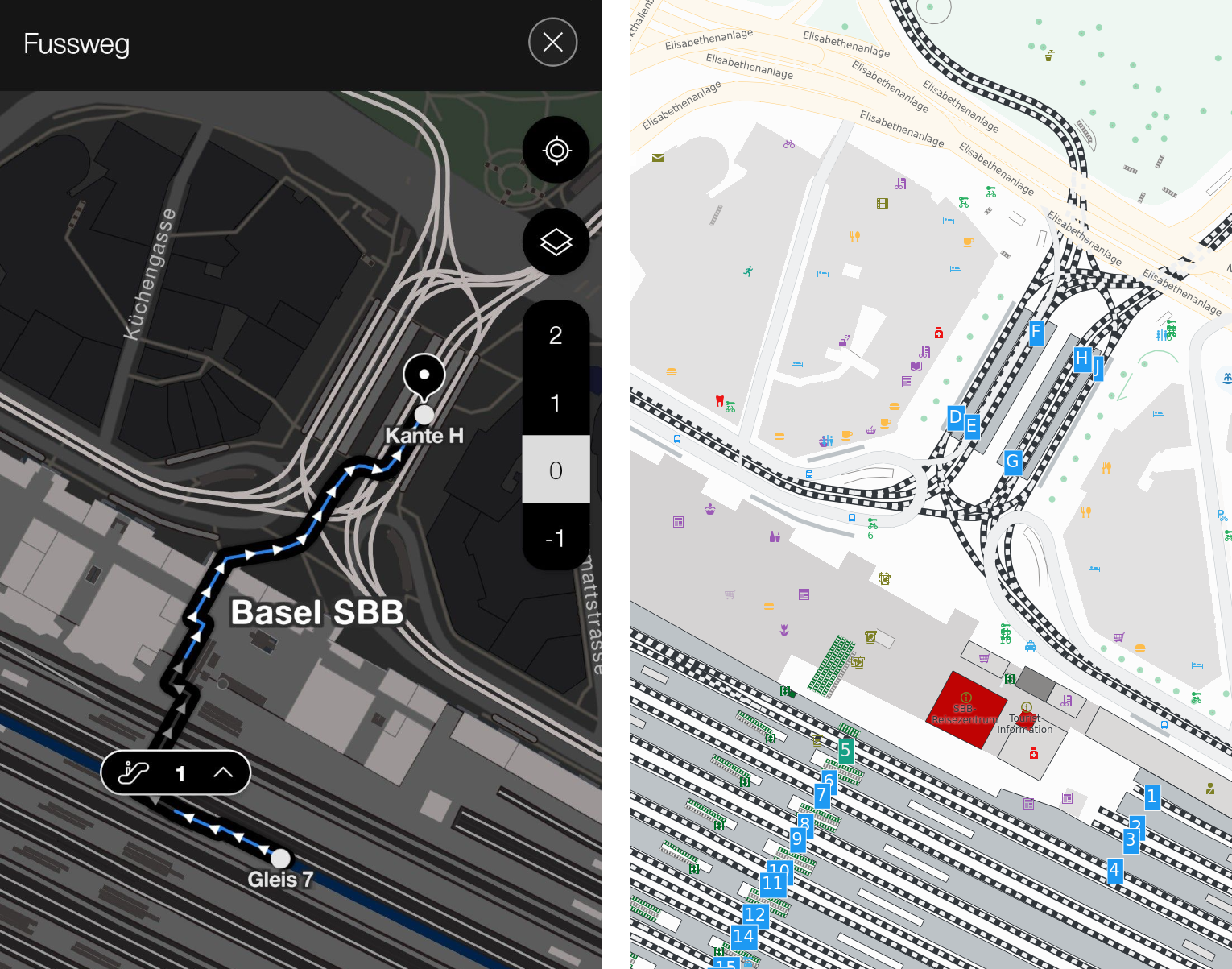

The best all-in-one free tool available for navigating stations that I know of is KDE Itinerary. While it focuses on general travel-planning, ticket-bookkeeping, and basically absorbing every use-case of any train operator’s in-house journey app except literally selling you tickets, it also displays station layouts, which it sources from Open Street Map (OSM).

Platform numbers are highlighted, complex multi-level station building layouts are displayed nicely, and whereever it can it integrates real-time APIs of station operators to display things like which elevators are currently out of order. More importantly for our problem, it can also give a list of all tracks in the station; useful for multi-level stations like Berlin Hbf, where not all platforms are immediately visible on a map.

DB InfraGO

But not for long! Starting next year, we’ll get yet another reshuffle of DB’s organisational chart, and DB Station & Service will cease to exist.

The official bahnhof.de website run by DB Station & Service, who operate the public-facing side of almost all train stations in Germany, likewise offer interactive station maps. These are again heavily based on OSM, but also source some of their information from elsewhere, presumably from DB itself. Notably, for larger stations they often include platform sections, information which is frequently absent in OSM. But more observations on that a little later.

Yet it misses out on some of KDE Itinerary’s nicest features: no live elevator status, no search for a given platform number, and no links to elsewhere. For a few stations, such as Berlin Hauptbahnhof, they additionally offer PDF maps, but these are rare.

Confusingly, they also don’t seem to advertise this website very much – multiple people I spoke to had no idea that it exists at all, even when they said it would’ve been very useful for them in the past.

Many other trip planning apps offer similar features, but are usually not nearly as sophisticated about it — e.g. Oeffi simply offers to open the station’s position in any third-party maps app that is installed.

Unfortunately, the only app I know to do actual in-station routing is SBB’s official mobile app, where that feature is limited to stations actually run by SBB itself.

And while all of them can be used to answer the question “are these tracks opposite of each other?”, they all do so as side-product of focusing on adjacent, more general themes. So why not build our own, special-purpose thing?

Getting raw data

NeTEx

In fact, there is a second alternative approach: EU Regulation 2017/1926 [EU17] requires all operators of public transport within the EU to publish timetable data in the NeTEx format, aggregated into one large data set per country. The European Commission maintains a list.

Unfortunately, these are true beasts: for Germany, it comes in at over 33GiB of pure XML, with wildly differing level of detail depending on line operators.

Perhaps I’ll manage to do something with it yet, but if so, that’s for a future post.

Since using OSM data seems to work out nicely for KDE Itinerary, I will here continue with that idea.

There is one pretty obvious alternative: Deutsche Bahn does run its own Open Data portal. It does not contain much, but there is in fact a data set describing platforms [DBStus20a]. Unfortunately, it has last been updated in 2020, and there seems little hope of regular yearly updates returning (my email about this went unanswered); and unlike with OSM, where the platforms are part of a much richer mapping effort, this data stands alone — so if we did use it, there’d be no easy way to connect it to anything else.

Data Model

OSM has three kinds of objects: nodes, ways, and relations, which can all have tags attached to them. Additionally, there is a membership relation between objects. Train stations usually look something like this:

- Individual platforms each get their own object, which have a

reforlocal_reftag giving their name (the difference between these two seems a little unclear; both are in frequent use for the same thing). For platforms which have no name (basically all in Germany) this is a semicolon-separated list of track numbers. - Platform edges are often (but not as universally) also mapped, and are then set as members of the platform.

- Platforms are part of a relation, which collects everything belonging to an entire station (along with walkways, shops, stairs, buildings, etc.).

- Stations also usually have a single “meta” node, on which we can find the

station’s name and various kinds of IDs. We will use the

railway:reftag, which contains “the operator’s internal abbreviation” of this station, and is widely mapped in OSM. - Finally, some stations are more complex than others: they may be split into smaller stations, have a local tram stop associated with them, or any manner of other things, which all result in a deeper nesting of membership relations.

So all we have to is to find a station’s meta node, walk through all the potentially messy forest of objects it’s associated with, and then grab everything that looks like a platform.

OverpassQL

OverpassXML

Actually, there is a second language, which the wiki suggest one use instead. But it’s XML-based and … eh, let’s look at the other thing instead.

It turns out that there is an entire language which exists solely to query data in OSM, which I had never encountered before.

Some of its design choices feel a little arcane (why does it limit almost all functions to names which are at most three characters long?), but otherwise I found it very pleasant to use.

Writing Queries

Learning Resources

The main wiki pages to read on the query language are the one on OverpassQL itself as well as its Language Guide.

[Hann20] also gives an introduction into the language. I wish I’d stumbled across this post before fiddling everything out using just the wiki.

A first attempt, using München Hauptbahnhof as a test case:

[out:json][timeout:25];

node["railway:ref"="MH"]["operator"~"^DB"];

rel["public_transport"="stop_area"](<);

nwr["railway"="platform"](>>);

out geom;It’s pretty easy to read, line-by-line: first we define general query parameters, such as the output format. After that, each line defines a statement which selects something.

- Select any node with

railway:refset toMHwhose operator’s name starts with “DB”; this is the station’s meta node. We can filter on tags with either=for simple equality, or~to match against a regular expression. - Then “walk up” the graph that node’s membership relations by one step (

<) to find the station’s meta-relation, which is tagged with"public_transport"="stop_area". - “Walk down” membership relations (

>>), and select everything that is tagged as a platform anywhere below this relation.

By default, the data “flows” implicitly from one line into the next: each statement

assigns its output to the “default variable” ._, and the next

statement reads from it. We could also write these explicitely and get a query

with the same semantics, like this:

[out:json][timeout:25];

node["railway:ref"="MH"]["operator"~"^DB"] -> ._;

rel["public_transport"="stop_area"](<._) -> ._;

nwr["railway"="platform"](>>._) -> ._;

out geom;In a bit, we’ll see more complex queries use custom variables.

For running test queries like this, it’s best to use overpass turbo.

Note that queries which don’t return any geographical features won’t show up

on the map; if your query seems to return an empty result, switch to the data

tab on the top right to see its result. On the other hand, should a query result

in an error, that is always shown.

For now, our query does not even find everything in München Hbf’s upper floor: both wing stations along with the underground S-Bahn station, are missing.

Wing stations are modelled in one of two ways: there is the railway:ref:parent

tag used for for stations which have a clear hierarchy between them: KKDT

‘belongs’ to KKDZ, MH N and MH S ‘belong’ to MH, etc.

Let’s incorporate that:

[out:json][timeout:25];

node[~"railway:ref|railway:ref:parent"~"^MH$"]["operator"~"^DB "];

relation["public_transport"="stop_area"](<);

nwr["railway"="platform"](>>);

out geom;This does almost the same as before, but in the first statement the simple

filter for equality of a tag has been replaced with one which matches tags

against a regular expression, marked as such by having a ~ in front.

This now catches both wing stations. But the S-Bahn is still missing.

To handle large, grouped stations, we need to more fully traverse the tree:

[out:json][timeout:25];

node[~"railway:ref|railway:ref:parent"~"^MH$"]["operator"~"^DB "];

relation["public_transport"~"stop_area|stop_area_group"](<<);

nwr["railway"="platform"](>>);

out geom;The above now uses the << operator, which gives the transitive closure of

membership relations upwards. This does indeed now find everything we wanted –

but using it is expensive: recursively walking upwards winds up traversing through

a lot of things we aren’t at all interested in. Unfortunately, there seems to

be no way to give a limit to that operation, nor can it filter out things as

it goes along: it first traverses everything, and only then starts applying the

filter.

This is bad. The query now takes several (5-15) seconds, even for relatively small stations.

Instead, we can use the rel(bn) and rel(br)

functions, which at least limit use to nodes and relations “on the go”, so we

won’t needlessly walk along ways (in our case, ‘ways’ have an unfortunate tendency

to model entire railway lines, greatly adding to needlessly-traversed data).

[out:json][timeout:25];

node[~"railway:ref|railway:ref:parent"~"^MH$"]["operator"~"^DB "];

rel["public_transport"~"stop_area|stop_area_group"](bn) -> .a;

rel["public_transport"~"stop_area|stop_area_group"](br.a) -> .b;

(.a;.b;);

nwr["railway"="platform"](>>);

out geom;This still finds the same as above, but takes much less time to run.

It now also uses named variables: to get both nodes and relations above the

original meta node, we first walk up to nodes using rel(bn) and

assign the result to the name .a, then walk up from that to relations using

rel(br.a), and give that the name .b.

The (.a;.b;) clause then merges both sets of objects, and assigns it back to

the default variable ._ as normal, so the next statement

can use it as its implicit input.

Testing

I deployed this version of the query to bahnhof.name almost a month ago now, and since then have received many pointers to stations where it failed to give any reasonable result.

In some cases this could be traced to things not being mapped in OSM at all — but often, there was something I had simply missed:

[out:json][timeout:25];

nwr[~"railway:ref|railway:ref:parent"~"^MH$"][operator~"^(DB|Deutsch)"];

(._;rel["public_transport"~"stop_area|stop_area_group"](bn);) -> .a;

rel["public_transport"~"stop_area|stop_area_group"](br.a) -> .b;

(.a;.b;);

nwr[railway=platform](>>);

out geom;Two major changes: one, there’s now an additional merge operation to keep the

original meta node when using rel(bn); otherwise some information

gets lost in a few cases.

The second change is perhaps more significant: the match against the operator

tag has become more complex — because although all passenger stations “run by Deutsche Bahn”

are operated by DB Netz AG on the railway-infrastructure side and by DB Station &

Service on the passenger side, there is no consensus at all how to refer to this

situation in OSM. The operator tag thus might contain variants of “DB Netze”

or “DB Station & Service”, or merely “DB” or “Deutsche Bahn”, or anything else

vaguely along these lines.

Since we use the railway:ref tag to identify stations, and these identifiers

are specific to Deutsche Bahn, there isn’t really much we can do about this

situation other than attempting to match as many variants as we can.

Catch them all?

It would be good to have some measure of certainty about how well this query works, as an attempt to measure its usefulness. What percentage of stations actually have platforms mapped and are found by our query?

Names are hard

railway:ref

This tag contains the “internal abbreviation”

used by a station’s operator; essentially, an ID for this station. As an example,

referring to Berlin's main station by BL is less ambiguous than “Berlin Hbf” or

“Berlin-Hauptbahnhof” or even the inexplicably still existing name “Berlin

Lehrter Bahnhof”

So far, I’ve avoided talking about how we find the stations in the first place:

via their Ril100 code, which in OSM is contained in the railway:ref tag.

Initially I wrote the queries to work with these because it was

convenient — I am familiar with the codes for stations I visit often, and they avoid

dealing with the fuzzier problems of station names.

Better IDs

There are better, more unique ways to address individual stations, such as Transmodel’s IFOPT standard, which gives IDs to every public transit stop (not just railway stations) in the EU [EN28701; VDV432], or UIC numbers, which give numbers to every station in Eurasia and northern Africa.

But these are less consistently tagged across OSM, so I decided not to rely on them.

Unfortunately, these codes have a major disadvantage: they are operator-specific, in our case to Deutsche Bahn. Within Germany, this seldom matters — almost all German station either are or historically were operated by Deutsche Bahn, and thus have their own unique Ril100 code.

But OSM is a global project — and figuring out if what is contained in railway:ref

is a Ril100 code or something specific to another operator isn’t trivial; limiting

the query to stations run by Deutsche Bahn is only a (bad) approximation. Nor

can we assume that railway:ref is a Ril100 code for every station in Germany,

and for none outside it — for complicated reasons, national rail operators

sometimes operate stations outside their ‘home’ country; DB’s best-known example

of these is probably Basel Badischer Bahnhof, which is in Switzerland.

Annoyingly, this means that all other stations anywhere else in the world are now automatically out of scope – and even the (rare) stations within Germany not operated by some branch of DB are missing.

So many Betriebsstellen

Even then, attempting to get a hold of the actual stations can be a little fuzzy. There is a complete list of all Ril100 codes [DBNetz21], but it does not match the usual intuitive meaning of “(passenger) railway stations”.

Betriebsstellen

Ril100 codes are primarily meant to designate Betriebsstellen, which for our purposes are an almost comically broad category – meant to describe the railway from the operator’s point of view [defined in Ril408], and are usually not exposed to the public at all.

A basic intuition for what has its own code is “thing which is in some way important for the railway’s operation outside of its immediate surroundings”. Thus, stations have a code, but generally not individual points within a station (but exceptions exist). Many other things have codes, too: signal boxes, crossovers, depots, electrical substations, repair shops, and even non-physical things like national borders. [DBNetz21] even includes one or two joke entries.

It just so happens they caught on in train nerd circles, as convenient and easily-remembered shorthands of stations.

Luckily, DB Station & Service also publishes a list of what they consider “stations”, also using Ril100 codes to identify them [DBStus20b]. This list comes much closer to what we want. But it’s important to keep in mind that it’s still not a complete match — though uncommon, there are still many stations or stopping points in Germany which are not operated by DB Station & Service, which are not included here. Especially smaller, regional stations are thus underrepresented.

Some Results

For the 5392 Ril100 codes contained in [DBStus20b], the query returned a

non-empty result containing at least one platform for 3551 stations, of which

3071 contained at least one ref or local_ref tag. So at least we got over

half of them — but there’s still a large gap.

It is, of course, somewhat hard to judge what happened with the 1841 stations for which nothing is found at all. At a glance, these skew heavily towards smaller stations — but I’ve not yet had time to go through at least some of them manually, and check whether they are simply not mapped at all in OSM, or mapped in some unexpected way which the query could not find.

More interesting are the 480 stations for which the query did find at least

one platform in OSM, but with no ref or local_ref tag. What sort of stations

are these?

Well, the majority (383 of them) have only a single platform, so the entire question of which connections are cross-platform becomes rather trivial.

The remaining 97 are a haphazard mix of still very-small stations, which are otherwise well-mapped but, for whatever reason, simply lack track numbers. The largest two, with four platforms each, are Herlasgrün and Großkorbetha, both in Saxony.

Somewhat hilariously, DB Station & Service’s official bahnhof.de website doesn’t have track numbers for these on their maps, either, perhaps suggesting that (at least for smaller stations) they do source their data entirely from OSM and do not have their own maps. On the other hand, we can definitely rule out that these tracks simply lack numbers entirely: on their accessability info, there is a list of tracks for both Herlasgrün and Großkorbetha – just without any information on which track is where.

Bahnhof.name

As mentioned, I happened to already have a small web service for quickly looking up Ril100 codes at bahnhof.name. At first I extended it with platform data by simply adding a static data set containing all platform data I could find in OSM — but it turns out you can’t simply publish a service backed by OSM data without people finding & fixing mistakes in the data it displays. So soon enough, I got people asking, “hey, how long will changes take to show up?”

So it now does dynamic updates instead, and caches results for a week. For no particularly well-explainable reason, I also decided this was a good opportunity to rewrite the entire thing in Haskell (before that and for even less-clear reasons, I’d originally written it in Gleam).

Gleam

Gleam is a typed language which compiles to Erlang. Overall it feels like a fun mashup of Haskell98’s type system with Rust’s syntax. However, it lacks type classes, and sometimes I found its syntax slightly inconvenient.

As a result, you can now look up a station’s platforms via e.g.

→ https://bahnhof.name/MH/tracks

for München Hauptbahnhof. If you find a mistake in OSM and decide to fix it, first of all, great! You can use

→ https://bahnhof.name/MH/fetch

to forcibly invalidate the cache and re-fetch platform data from OSM afterwards.

Possible improvements

There are some exciting ways in which this could be extended:

For one thing, lifting the restriction on DB-run stations would be great. This shouldn’t be too hard — if push comes to shove, one can always look up a station by its name — but neither is it entirely trivial. As mentioned, there are more universally applicable station ID standards (in the shape of IFOPT or UIC numbers) — but so far, these are not as widely used in OSM.

Much more complicated (but very useful) would be an attempt to create a kind of inside-station routing engine, akin to that which the SBB’s app already has. As far as I’m aware, this is probably not possible with the data that is (currently) contained in OSM. Perhaps it would be possible to integrate data from the official NeTEx data set — but matching that against the OSM data looks like a daunting task.

Finally, for now there is one thing missing entirely: information on platform sections (in Germany, usually designated A through G, with fewer sections on shorter platforms). These would be especially useful, as many other passenger information systems will tell you in which platform section your carriage will stop — but for now, these are seemingly not modelled in OSM at all, and I don’t even know where I’d begin if I wanted to add them.

EDIT: the above is incorrect! Thanks to trissc̈hen

for pointing out to me that the railway:platform:section tag exists, which I’d

overlooked before.

Conclusion

Go have fun, and hopefully worry slightly less about your tightly-planned travel itinerary!

I might revisit this some other time, or implement some of the ideas in the section above — but well, we’ll see, and for now I’ll make no promises. In the meantime, if you have ideas or improvements, feel free to poke me. I’ll also gladly accept patches for bahnhof.name’s source code.

Many thanks to many wonderful friends who helped point out things to me on the way, to Moira for patiently answering my questions about what kinds of Betriebstellen exist, to networkException for all their suggestions and for getting me to do live updates, to FireFly and some friendly dragons for listening to all my ramblings about NeTEx, OSM, and obscure stations (and asking helpful questions along the way), to Fynn and everyone else who pointed out mistakes in the initial query’s results, and especially thanks to everyone who has contributed to the station data contained in OSM!